Citation: Enwerem NM et al. Editorial: Food-Drug Interactions: Implications for Nursing Practice. Nurs Health Care Int J 2017, 1(1): 000102.

*Corresponding author: Nkechi M Enwerem, College of Nursing and Allied Health, Howard University, Washington DC 20059, HRSA, Division of State HIV/AIDS Programs (DSHAP),5600 Fishers Lane, Mail Stop 09W53B,Rockville, Maryland 20857, USA, Tel: 202-806-5522; Email: nkechi.enwerem@howard.edu

Background: Registered nurses (RNs) play important roles in patient safety.Medication errors resulting in adverse drug reactions (ADRs) pose a significant public health problem. A safety concern, which can lead to treatment failure, is concurrently administering drugs and foods which interact negatively. For example, administering warfarin and foods rich in vitamin K together result in pharmacodynamic antagonism of the warfarin. Studies on the knowledge, attitudes and awareness of food and drug interactions (FDIs) among nurses with different educational levels are lacking. The purpose of this study wasto ascertain the knowledge, awareness and attitudes of RNs regarding FDIs, and to investigate the relationship between their educational levels and their scores on the Nurses’ Knowledge, Awareness and Attitudes Survey.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional descriptive study which included a structured questionnaire with emphasis on common FDIs found in medical journals. The study protocol was approved by the Howard University Institutional Review Board. The FDI questionnaire consists of 40 questions (including dichotomous, multiple choice and open-ended questions). The study included a convenience sample of 278 nurses divided into 3 groups (82 with associate degrees, 151 with baccalaureate degrees, and 45 with graduate degrees). Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). The Neuman Systems Model provided the theoretical framework for the study.

Results: Twenty-two percent (22%) of the participants were male, and seventy-eight percent (78%) were female. There was no statistically significant relationship between knowledge and practice of FDI among the 3 groups. Of the 72% of nurses who had not observed food and drug interaction during their practice, 80.5% were associate degree holders, 73.5% had baccalaureate degrees, and 53% had earned graduate degrees. There were no significant differences in FDI knowledge scores among the associate degree, baccalaureate degree and graduate degree prepared nurses. The level of awareness of adverse effects resulting from FDIs was directly related to the level of nurses’ education. About 28% of the study participants had recorded FDIs during their clinical practice. Nurses prepared at the graduate degree level, had witnessed more FDIs than the associate and baccalaureate degree holders.

Conclusions: The results of this study showed that nursing health care professionals exhibit a low knowledge of FDI. The low scores observed, suggest that knowledge and attitude deficits continue to exist. Education exposes a nurse to different possible FDIs. Most of the participants recommended in-house training on FDI every six (6) months. The authors are aware that demographic characteristics such as the unit in which the nurses practice, full time or part-time and the type of organizationmay influence a nurse’s knowledge, practice and awareness of FDIs. It is recommended that future studies on this subject include larger sample sizes.

Keywords: Food and drug interactions; Knowledge, Attitudes, and Awareness; Nurses educational levels (Associate, Baccalaureate, Graduate degrees); Neumann Systems Model

Food and drug interactions (FDIs) occur when specific nutrients in foods interact with drugs if ingested concomitantly. FDIs can result in changes in the bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and therapeutic efficacy of medications. For example, dietary sources of vitamin K, such as spinach or broccoli, have been shown when consumed in large quantity, to lead to pharmacodynamics antagonism of warfarin [1,2]. Such effectwill result in a need to increase the dosage of warfarin. Grapefruit juice contains a bioflavonoid that inhibits cytochrome P4503A enzyme (CYP3A) which is involved in the metabolism of many drugs [3,4]. The coadministration of a drug that is metabolized by CYP3A such as felodipine with grapefruitjuice, can cause a 5-fold increasein the plasma concentration of such drugs [4,5]. Patients at high risk for FDIs include elderly patients taking three or more medications (polypharmacy) for chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, depression, high blood cholesterol, or congestive heart failure.

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine reported that as many as 98,000 deaths occur annually in US from medical errors [6,7]. In the United States, the cost of managing drug-related morbidity and mortality is about $37.6 billion annually [8,9]. About half of the cost, is associated with preventable errors [10].

FDIs pose a significant public health problem. Several studies confirm that Registered Nurses, play important roles in patient safety [8,11,12]. The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) requires that a thorough drug history be taken during hospital admission, as well as adequate drug reconciliation during discharge [13]. JCAHO recommends that nurses should be alert in monitoring for possible FDIs, provideguidance to patients on food and beverages to avoid when on certain medications.To function effectively in this role, nurses have to be adequately trained and be current on possible FDIs. Career development occurs through formal education or continuing education or on-the job experience.

Nursing is a profession that has more than one level of educational preparation. These include diploma, associate degree, baccalaureate degree, and graduate degree (master’s and doctoral) levels. Severalrecommendations have been made to establish the minimum requirement for entry into registered nursing professional practice as the baccalaureate degree [14-16]. In 2010, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation working with the Institute of Medicine issued a statement that by 2020, there should be an increase of nurses with baccalaureate degrees from 50 to 80%, while the number of nurses with doctoral degrees should double within this period [17]. The fulfillment of academic progression from associate degrees to baccalaureate degrees is slow in the US [17,18].

Continuing Education (CE), a lifelong learning experience, helps nurses to keep abreast of the constantly changing and progressive new theories on diseases, technological advances, patient care trends, new and revised protocols, medical breakthroughs and research findings. The American Nurses Association defined CE as "learning activities designed to augment the knowledge, skill and attitudes of nurses and as a result, enrich the nurses' contributions to quality healthcare" [19]. Participationin CE activities have been shown to lead to safer patient care [20], positive patient outcomes, increased knowledge in the area of practice, and improved critical thinking [19,21]. CE can be obtained through formal or informal education such as conferences, seminars, and in-service training [19].

The need for CE on FDIs is exemplified by the work of Enwerem and [22] on the knowledge, attitude and awareness of FDIs among nurses. The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to examine the knowledge of FDIs in their day-to-day practiceamong nurses with different levels of experience. The study included a sample of 278 nurses with different levels of experience: 0-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years, 15-19 years and ≥ 20 years.Their study,results revealed a low knowledge of FDIs in all five groups studied.

Neumann’s System’s Model Theory of Nursing provided the theoretical framework for the present study [1]. This framework addresses the concepts of treatment failure from FDIs. In an individual who has an unstable health system as a result of a loss in the line of defense, brought into the health care system.Primary, secondary or tertiary preventive measures are instituted to restore stability. The components of the Systems Model Theory employed for this study areillness and prevention as intervention. To prevent treatment failure from FDIs, the nurse needs an adequate knowledge of foods that interactwith drugs, and the pharmacokinetic processes of drug administration. This knowledge basedinformation comes from the nurse’s previous education and experiences. The nurse’s attitude and awareness regarding FDIs also play a role in her/his ability to educate the patient on the timing of food and drug use, foods that interacts with certain drugs, and the signs and symptoms of adverse effects from such interactions.Consequently, the nurse needs a good knowledge of FDIs to meet the needs of his or her patients.With increased knowledge gained by CE, the nurse’s ability to offer education on consequences of FDIs wouldincrease.

This study examined the differences, in the knowledge, attitude, and awareness of FDIs amongnurses prepared at the associate, baccalaureate and graduate degree levels.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional descriptive survey using the validated, structured questionnaire of Jyoti et al. [23] (Appendix I). The questionnaire is focused on common FDIs.

The target population for this study was registered nurses (RNs) from health care facilities in the District of Columbia Metropolitan (DC-MD-VA) area. The study was approved by the Howard University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The questionnaires were distributed to the RNs, who were asked if they would participate in a study to test their knowledge of FDIs. Those that indicated interest were asked to sign the IRB-approved consent form (Appendix II). The study was carried out during the period of March–December 2014.

The size of this convenience sample was 278. The sample included three groups of RNs with different levels of academic preparation (82 with associate degrees, 151 with baccalaureate degrees, and 45 with graduate degrees).

Data CollectionThe FDI questionnaire (FDIQ) developed by Jyoti et al. [23] was used for this study (Appendix I). Written permission for use of the questionnaire was sent to the corresponding author.

The FDIQis a 40-item tool with dichotomous, multiple choice and open-ended questions were included in the questionnaire.Of the 40 questions, 35 tested participants’ knowledge (Appendix II) and 4 determined participants’ attitudesregarding preventing FDIs in their health care organization. (Appendix III). One open-ended question was incorporated to obtain participants’ suggestions on the steps to take to increase their knowledge, awareness and practice of FDI. The FDIQ included questions regarding food interactions with antihypertensive, antithyroids, antidepressants, anticoagulants, antiretrovirals, peptic ulcer drugs and analgesics. The FDIQ also measured if the participant had noticed any food and drug interaction during their practice. On average it took 30 minutes for participants to complete the questionnaire. Personal identifiers were excluded from the questionnaire.

Data AnalysisStatistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics (SPSS) Version 22 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Results were expressed as mean ± SD. The 35 knowledge-based questions were equally weighted. Questions answered correctly were each awarded one point, while incorrect answerswere given zero points. The maximum score for the knowledge questions on FDIs was 35 while the maximum score for practice questions was 4. Therefore, a higher score indicates a higher number of correct responses on the survey. The Pearson’s chi-square test followed by the Mann-Whitney U test, were used to evaluate homogeneity of the data across the groups. Oneway Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the total score among the different groups. A two-way ANOVA was conducted, to examine the effect of education and experience of nurses on the ability to identify (observation or awareness) of food and drug interaction. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

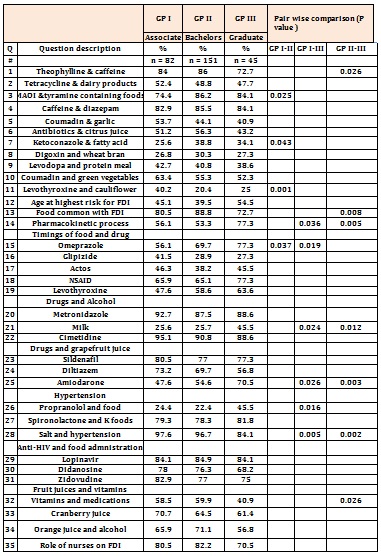

ResultsThe survey was completed within nine months of the start of the study. The response rate was 100%, and all participants completed the FDIQ within 30 minutes. The overall knowledge of the study participants was assessed based on their responses to the questionnaire (Appendix I; Appendix II). Table 1 shows the knowledge and comparison of the FDIQ among associate, bachelor’s and graduate degree nurses. The values reported for each question represent the percentages of the correct answers in each of the groups. With respect to timings of food and drug intake, most of the participants, were conversant with proton pump inhibitors (PPI e.g. omeprazole), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and thyroid hormones (levothyroxine), but were not aware of the antidiabetic drugs such as acarbose, glipizide, antacids, and drugs for tuberculosis (isoniazid) (Qs 15 & 16). For these drugs, participants with associate degrees, scored better than baccalaureate and graduate degree holders. For the question on the interaction of coumadin with ginger or garlic (Q5), all of the participants scored low. Concerning the interaction of theophylline with large amounts of tea, coffee and chocolates (Q1), graduate degree prepared nurses, scored lower. Associate degree holders scored low regarding tyramine containing food such as, cheese, processed meats, legumes, wine, beer, fava beans and fermented products with MAO inhibitors (Q3), as well as on the knowledge of the interaction of griseofulvin, ketoconazole and albendazole with fatty diets (Q7) and on the pharmacokinetic process where FDIs occur most (Q14). This group scored better than the baccalaureate- and graduate degree-prepared nurses on the interaction of thyroid supplements with foods such as brussels sprouts, cauliflower, millet and cabbage (Q11).

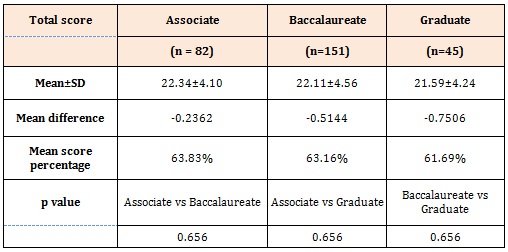

The three groups scored low on the interaction of digoxin with foods such as wheat bran, rolled oats and sunflower seeds (Q8), ketoconazole and fatty acid (7), interaction of alcohol and milk (Q21) and on the interaction of propranolol and food (Q26). The graduateprepared nurses scored high on the interaction of amiodarone with grapefruit juice (Q25). There was no significant difference among the three groups on their knowledge of the interaction between diltiazem and grapefruit juice (Q24). The total scores on the knowledge test as displayed in Table 2 were as follows: associate degrees (22.3±4.1), baccalaureate degrees (22.1±4.6), and graduate degrees (21.6 ± 4.2). No significant differences in knowledge were found among the three groups.

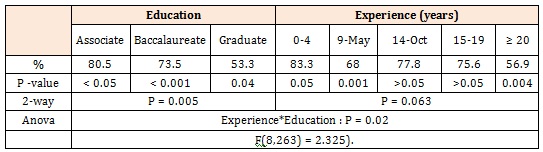

AwarenessMost of the participants (72.3%) had not observed adverse reactions due to FDIs during their clinical practice. Significant differences occurred between the groups. Associate degrees (80.5%; p<0.05), baccalaureate degrees (73.5%; p< 0.001) and graduate degrees (53.3%; p=0.004) (Table 5). Nurses prepared at the graduate degree level had observed FDIs more thanthe other groups. This is followed by nurses with baccalaureate degrees. Two-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant difference in the number of FDIs observed among the nurses prepared at different educational level. However, there were significant differences in the number of adverse reactions observed during practice among nurses of different levels of education (P – 0.005 < 0.05). The interaction between the education and experience of nurses’ on the number of adverse effects observed fromFDIs was positive (P – 0.02 < 0.05; F (8.263) = 2.325) (see Table 5).

From the open-ended question on how knowledge and awareness of FDI may be improved, most of the participants felt it is important to update knowledge of FDIs every six months through in-service training.

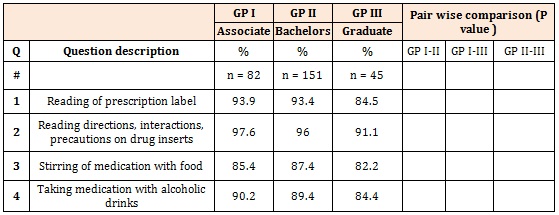

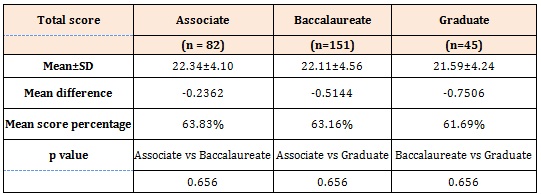

AttitudeTables 3 and 4 revealed that the overwhelming majority of the nurses in the three groups agreed with the steps that should be taken to prevent FDIs. The participants agreed that before a drug is dispensed, the label on the container should be read, and the package inserts listing the directions for use, interactions and precautions should be read. Furthermore, the participants believe that medications should not be taken with alcohol. With respect to practice, nurses prepared at the associate degree level took time to understand the drug with respect to drug interactions and drug administration before giving clients their medication (Table 3).

DiscussionThe present study was successful in evaluating the knowledge, awareness, and attitudetoward FDIs among nurses prepared at varying levels of education. With respect to knowledge of FDIs, there were no significant differences among nurses prepared at the associate, baccalaureate and graduate degree levels. However, there were significant differences on some individual questions such as interaction of theophylline with caffeine (Q1), Coumadin with garlic (Q5), and digoxin with fiber (Q8).

Table 5 showed that nurses prepared at the graduate degree level more frequently observed FDIs compared to the other groups. This is followed by nurses with baccalaureate degrees. These differences could be due to the higher level of clinical preparation which helps nurses prepared at graduate and baccalaureate degree levels to be equipped to identify adverse reactions resulting from FDIs. The 2–way ANOVA test confirms that there is an interaction between education and the ability to identify adverse reactions resulting from FDI (See Table 5). These findings may suggest that the level of education affects a nurse’s ability to differentiate adverse reactions resulting from FDIs fromother causes.The results of this study with respect to the awareness (observation) of FDIs are in line with the results of other studies that have shown that the level of education is strongly correlated to patient safety [24,8]. Nurses with higher education do better in recognizing FDIs.In the IOM report (2010) [8], it is recommended that there be anincrease in the proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree to 80 percent by the year 2020. Academic nurse leaders across all schools of nursing were urged to work together to increase the proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree from 50 to 80 percent by 2020. This gap in knowledge can also be bridged through informal continuing education such as attending conferences and in-service training.

Drug interaction does not only occur between two drugs. They can occur between drugs and any type of foreign substance (xenobiotic) or food (e.g. grapefruit juice, broccoli, and barbecued meats), caffeine and alcohol [25]. Warfarin interactswith vitamin K rich vegetables, such as broccoli, kale, and spinach, when consumed in large quantity [26,27]. FDIs occur when the presence of a food changes the bioavailability of a drug co-administered together. This variation can result in therapeutic failure especially with orally administered drugs [28]. Foods can change drug bioavailability through various mechanisms which include changes in gastric emptying and in the activity of drug metabolizing enzymes [29]. Improper timing of foods and drugs are contributors to treatment failure [23]. Elderly patients on polypharmacy, should be assessed regularly for FDIs [28].

The participants from the three groups scored very low in some questions on the FDIQ such as the timing of foods and drugs. Questions such as should propranolol, ACE inhibitors, glipizide, isoniazid, antacids, acarbose, voglibose be taken with or without food. To enhance therapeutic effects, drugs such as glipizide, atenolol, captopril, isoniazid, and rifampicin that interact with foods should be taken on an empty stomach [30,31]. Nazari AM [32], showed that the administration of captopril on an empty stomach will decrease its absorption significantly. The three groups scored low on their knowledge of the interaction of food with alcohol, and with antihistamine drugs such as cimetidine. Acute ethanol absorption inhibits drug metabolism. Chronic alcohol consumption affect the plasma concentration of drugs consumed orally or through the parenteral route [33].

The three studied groups especially nurses with associate degrees, scored poorly on the interaction of griseofulvin, ketoconazole and albendazole with fatty diets. These drugs have antifungal and anti-worm properties. Earlier studies have shown that these drugs are poorly absorbed when administered orally [34]. A high systemic concentration is observed when these drugs are co-administered with a fatty food [34]. The maximum plasma concentration of griseofulvin increased by 80% in the presence of high fat meals. This increase is a result of enhanced solubilization of griseofulvin by fat [35]. Drugs with a large therapeutic index produce harmless effects when they interact with food [5]. Griseofulvin has a wide therapeutic index. However, at a high concentration, toxicity is observed because of concentration-dependent liver enzyme induction. Albendazole exhibits similar characteristics to griseofulvin in the presence of a fatty meal. Unlike griseofulvin, a high carbohydrate, low fat meal significantly reduces the plasma concentration of ketoconazole and albendazole [36].

Drugs with low therapeutic index are more likely to produce a significant harmful effect when they interact with food [5]. The three groups of participants, scored low in the interaction of digoxin with foods such as wheat bran, rolled oats and sunflower seeds. Digoxin is a drug that is commonly used in the management of atrial arrhythmias and congestive heart failure. Agents that affect intestinal motility have been shown to affect the rate and extent of absorption of orally administered digoxin [37]. Johnson FB [38] showed, in sixteen healthy volunteers, concurrent administration of digoxin tablets with a meal high in fiber decreased the extent of absorption of digoxin. Digoxin has a narrow therapeutic index. Therefore, changes in the bioavailability of digoxin will have a significant therapeutic effect. The consequence of a decrease in the plasma concentration of digoxin will lead to therapy failure. Drugs with low therapeutic indices such as phenytoin should be taken at set times in relation to meals [26,39,40].

The groups did poorly on the interaction of levodopa with a meal rich in protein. Levodopa is used in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Its absorption from the small intestine is mediated through an unknown large neutral amino acids transport pump [41]. The coadministration of levodopa with dietary amino acids causes an increase in the competition for transport in the small intestine and at the blood-brain barrier, thus decreasing the bioavailability of levodopa [41]. Question 14 tested participants on the pharmacokinetic process where interactions occur most. Associate degreeprepared nurses scored low on this question. Similar scores were noticed on the effect of grapefruit juice on amiodarone. Associate degree-prepared nurses scored better than the baccalaureate- and graduate degreeprepared nurses on question 11 on the interaction of levothyroxine with foods such as cauliflower.

ConclusionsThe results of the present study support those from other studies that have shown significant differences in the impact of nursing education on patient safety [8,24]. The study revealed that the level of awareness of FDIs is directly related to the level of nurses’ education. About 28% of the study participants had recorded FDIs during their clinical practice. Nurses prepared at the graduate degree level had witnessed more FDIs than the associate and the baccalaureate degree holders. The present study showed that there is no significant difference in the knowledge of FDIs amongst the associate degree, baccalaureate degree and graduate degree prepared nurses. However, some significant differences were observed for certain questions as the interaction of theophylline with caffeine (Q1), coumadin with garlic (Q5), and digoxin with fiber (Q8). However, the total score differences were not significantly different.

The low scores observed suggest that knowledge and attitude deficits continue to exist. The study findings support the need for nurses to update their practice through advancement in preparation, attendingprofessional conferences, and engagement in continuing education programs. The authors are aware that demographic characteristics such as the unit in which the nurse practice, full-time or part-time employment, and the employment setting will affect a nurse’s knowledge, practice and awareness of FDIs. The authors recommend that future studies focus on these variables with larger sample sizes. Also, future research should include assessment of FDI knowledge, practice and awareness among nurses working in different clinical units, and nurses working in different types of facility (hospital, nursing home). Regression and propensity analyses are recommended to more adequately address interactions among variables.

Study LimitationsLimitations of this study include the small sample size and duration of recruitment.

Table 1: Comparison of the knowledge of FDI in the three groups (associate degrees, baccalaureate degrees, and graduate degrees): Expressed as percentage of respondents with correct answers for each question).

Table 2: Total score, mean difference and the mean score percentage of knowledge of FDI among the three groups.

Table 3: Comparison of the Attitude of FDI in three groups (associate degree, baccalaureate degrees, and graduate degrees): Expressed as percentage of respondents with correct answers for each question.

Table 4: Total score, mean difference and the mean score percentage of Attitude to FDI among three groups.

Table 5: Regression studies: Nurses who have not observed FDI in their clinical practice.

Chat with us on WhatsApp